WWW.PROPUBLICA.ORG

Utah Sen. Mike Lee Says Selling Off Public Lands Will Solve the Wests Housing Crisis. Past Sales Show Otherwise.

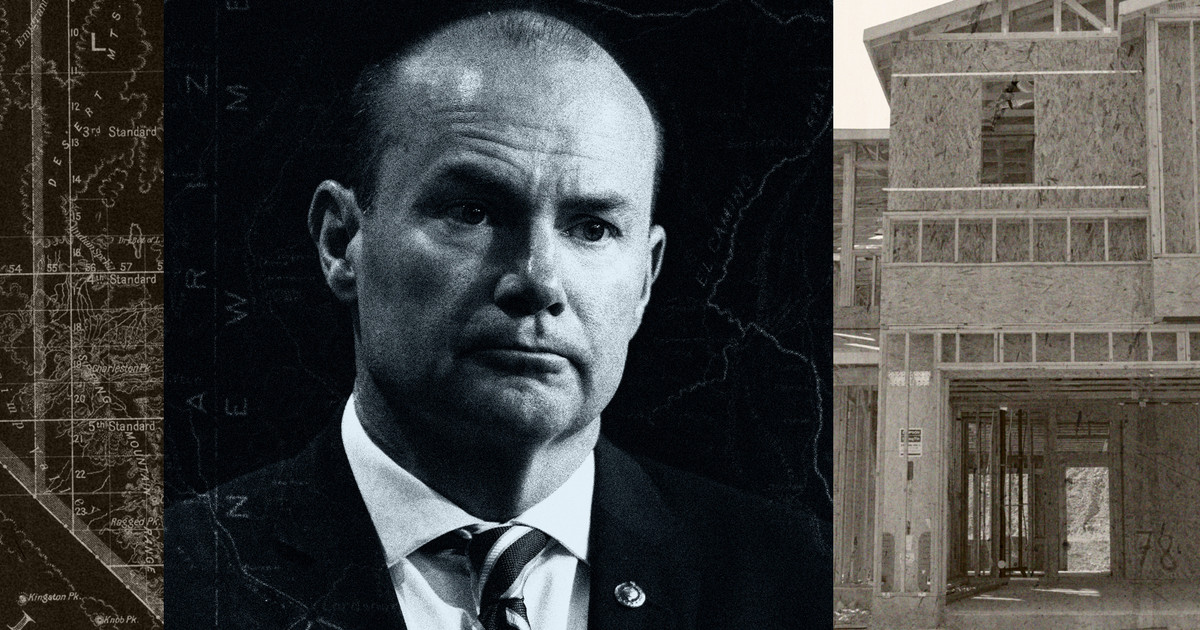

by Abe Streep ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week. On Monday, June 23, a crowd of about 2,000 people surrounded the Eldorado Hotel & Spa in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where members of President Donald Trumps Cabinet had come for a meeting of the Western Governors Association. Not for sale! the crowd boomed. Not one acre! There were ranchers and writers in attendance, as well as employees of Los Alamos National Laboratory, all of whom use public land to hike, hunt and fish. Inside the hotel ballroom where the governors had gathered, Michelle Lujan Grisham, the New Mexico governor, apologized for the noise but not the message. New Mexicans are really loud, she said.On the street, one sign read Defend Public Lands, with an image of an assault rifle. Others bore creative and bilingual profanities directed at Trump, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum, who oversees most of the countrys public acreage, and Sen. Mike Lee, the Republican from Utah, who on June 11 had proposed a large-scale selloff of public lands. Lee, who chairs the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, was not in Santa Fe, so the crowd focused on Burgum, who earlier that afternoon had addressed the governors about energy dominance and artificial intelligence. Show your face! the crowd chanted. But he had already departed the hotel through a back door. That night, a hunting group projected an image of him on the exterior wall of the hotel. Burgled by Burgum, it read.In the weeks before the meeting, the possibility of selling off large swaths of public lands had seemed as likely as at any time since the Reagan administration. On June 11, Lee had introduced an amendment to the megabill Congress was debating to reconcile the national budget. The amendment mandated the sale of up to 3 million acres of land controlled by the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management, with the vast majority of proceeds going to pay for tax cuts. Although Lee had framed his measure as a solution to the Wests acute lack of affordable housing, it would have allowed developers to select the land they most desired. Under the amendments original language, the ultimate power to nominate parcels for sale fell to Burgum and Brooke Rollins, head of the Department of Agriculture, which oversees the U.S. Forest Service.In the days after the Santa Fe protest, the outcry from hunting and outdoor recreation groups escalated across the West and the Senate parliamentarian ruled that Lees amendment violated the chambers rules. Republican lawmakers from Montana opposed the amendment; Burgum also distanced himself from it. (It doesnt matter to me at all if its part of this bill, he told a reporter on June 26.)By the time Burgum made his comments, Lees effort seemed doomed, and days later he announced that he was removing the amendment; public land advocates celebrated. This win belongs to the hunters, anglers, and public landowners, wrote Patrick Berry, the president of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. But the celebration may have been premature. In a social media post announcing his decision, Lee indicated that he would revisit the issue: I continue to believe the federal government owns far too much land, he wrote. And powerful forces still support privatization. At the Santa Fe gathering, Rollins had been asked during a press conference about the effort to sell federal land. She told reporters she wasnt familiar with the specifics of Lees amendment but supported his broader vision and suggested such efforts will continue regardless of the fate of the amendment. Half of the land in the West is owned by the federal government, said Rollins. Is that really the right solution for the American people? Protestors gather outside the Eldorado Hotel & Spa in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the Western Governors Association conference was held in June. (Dave Cox/Searchlight New Mexico) The circumstances that led to Lees proposal continue to simmer. The American West has an acute lack of affordable and attainable housing. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Colorado, with a population of 6 million, is lacking 175,000 rental units for people who earn up to 50% of area median income. New Mexico, which has one-third of Colorados population, is lacking 52,000 such rentals; Utah, 61,000. But nowhere is the issue as acute as in Nevada, where Las Vegas and Reno are encircled by public land. The state of 3.27 million is estimated to lack 118,000 such rentals.The lack of housing emerged as a lever for Lee, who has sought to challenge federal control of public lands since he was first elected to the Senate in 2010. A year after winning his seat, he introduced a bill to sell a limited amount of public land, saying, There is no critical need for the federal government to hold onto it. In 2013, he and others in his states delegation wrote a letter demanding the transfer of federal lands to Utah and angrily accusing the Bureau of Land Management, which manages 245 million acres nationwide, of obvious abuse. And in a 2018 address at a think tank, he compared federal land managers and people who recreate on public acreage to feudal lords, ruling from far-off kingdoms on the coasts. He also denounced elite publications that advocated for the protection of public lands, and he used the language of political war to describe the conflict over federal land: It will take years, and the fight will be brutal. (Lees office did not respond to detailed questions from ProPublica.)But this spring, Lee found support from unlikely places: the coastal elites he previously railed against seemed open to some of his ideas. The arguments in favor of privatization and development use a word of the season: abundance. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompsons bestselling book of the same name argues that burdensome regulatory processes have crushed the American housing market. While the authors focus on increasing supply in urban areas, in April, The New York Times ran an op-ed calling for building housing on public lands. That same week, the Times Magazine, in a piece titled Why America Should Sprawl, framed outward growth, including through the sale of public lands, as all but inevitable. The American Enterprise Institute, a free-market think tank, has estimated that the nation could build 3 million homes by opening federal land. In December, AEI leaders advocated for federal land sales in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, promising that disposal could usher in housing abundance and prosperity.When pitching his land-sale bill, Lee adopted a more moderate tone than in years past, focusing squarely on housing. On June 20, he posted on X, This is to help American families afford a home. On June 23: Housing prices are crushing families. The next day: This land must go to American families. But its challenging to build affordable housing on public land for a host of reasons, among them the high cost of infrastructure such as water pipelines and the cumbersome bureaucratic processes involving land agencies. But a primary obstacle is the price of that land itself: When its sold at market rate, its extremely difficult for developers to create affordable homes. High land costs alone can kill an otherwise great affordable housing project, said Waldon Swenson, vice president of corporate affairs for Nevada HAND, which builds affordable rental housing.In fact, past public land sales have created very little affordable housing. Theres just one prominent test case, in Nevada, where a 1998 law enables the sale of federal land at market rate in the Las Vegas Valley and at steeply discounted prices throughout the state if its to be used for affordable housing. Though municipalities can buy BLM land at $100 per acre to create affordable housing, the law has so far created just about 850 affordable units on 30 acres of land. By contrast, the laws market-value mechanism has enabled the sale of more than 17,000 acres of land at an average of more than $200,000 per acre. In March, the BLM sold 42 acres for $16.6 million. Meanwhile, according to a recent analysis, rents in Clark and Washoe counties have respectively risen by 56% and 47% since 2018. Lees amendment did little to address these issues and lacked any definition of affordable or attainable housing. Furthermore, it allowed private developers to nominate parcels for sale at market rate only. It would be an unmitigated disaster, wrote Mark Squillace, a professor of natural resources law at the University of Colorado law school. John Leshy, a former solicitor for the Department of the Interior during the Clinton administration and an emeritus professor at the University of California College of the Law, San Francisco, said that the bill was not a well-designed scheme to get more acres out there built with affordable houses. Leshy, the author of Our Common Ground: A History of Americas Public Lands, added, I think it is just a ploy to get your toe in the door to start selling off lots of federal land. New houses were going up in Henderson, Nevada, in February. A 1998 law allows the sale of federal land at market rate in the Las Vegas Valley and at deep discounts throughout the state if its to be used for affordable housing, which has led to the construction of some new units. (Sam Morris/Las Vegas Review-Journal/Tribune News Service/Getty Images) Congress stance toward public land shifted as settlers moved westward, violently displacing tribal nations. During the homesteading era, the General Land Office a precursor to the BLM was tasked with disposing of federal lands to states. But in the late 19th century, states began to request that Congress set aside lands for national forests. As a condition of its statehood, in 1896 Utah relinquished any claim to ownership of unappropriated public lands an acknowledgment that appears in its state Constitution. As the conservation movement took off in the early 20th century, lawmakers and presidents set aside more public land. In 1976, Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which codified the BLMs role in stewarding lands and declared that they would remain public unless their sale served the national interest.Lee has lamented the impact of those historic changes on Utah, where 42% of the state is BLM land, saying in a 2018 speech, Manifest destiny had left us behind, in some respects.A movement in the 1970s tried to reverse those historical currents when Western ranchers and lawmakers calling themselves Sagebrush Rebels sought to claim federal lands for states. They found sympathetic ears in Washington, D.C.: Ronald Reagan, during a 1980 campaign stop in Salt Lake City, said, Count me in as a rebel. Once elected, he nominated as secretary of the Interior James Watt, an attorney who favored transfer of public lands to the states. Reagan also came to rely on an economic adviser named Steve H. Hanke, who arrived at the White House from Johns Hopkins University. Hanke was more strident about getting rid of public lands than Watt; he has written that public lands represent a huge socialist anomaly in Americas capitalist system.Hanke helped drive an ambitious effort to dispose of national forests and grazing lands, and in 1982 the Interior Department announced plans to sell millions of acres as much as 5% of the public estate in order to reduce the national debt. Hanke later joined The Heritage Foundation, entrenching the idea of privatizing lands at the conservative think tank and predicting that Americans would come around to his way of thinking. Since then, the foundation has regularly advocated for selling public lands. (The foundation did not respond to inquiries from ProPublica.)Lee is deeply tied into The Heritage Foundation, which he has called a guiding light for generations. In 2016, The Heritage Foundation suggested that Trump nominate Lee to the Supreme Court. Among Utahs leadership, his positions on federal land are widely held. Last year, the state attorney general filed suit to the United States Supreme Court, seeking to seize 18.5 million acres of federal public land. The court declined to hear the case.Public lands are popular, especially among hunters, hikers and off-roaders, and periodic efforts to sell them have incurred wrath. In 2017, Jason Chaffetz, the former Utah representative, retracted a disposal bill after a backlash. Last December, a survey of 500 Utah voters commissioned by the nonprofit Grand Canyon Trust found that a majority of both Democrats and Republicans supported preserving national monuments in the state. In its preelection policy recommendation known as Project 2025, The Heritage Foundation called for the privatization of everything from public education, using school-choice programs, to Medicare, by automatically enrolling patients in insurer-run plans. But it notably didnt call for the privatization of the public estate.Instead, Lee has recently focused the debate on affordable housing. In 2022 and 2023, Lee introduced legislation to sell Western lands called the HOUSES Act. The bill was more prescriptive than his reconciliation amendment: It only allowed states and municipalities to nominate lands for disposal, rather than developers, and it required that 85% of nominated parcels be developed as residential housing, at a minimum of four homes per acre, or as parks. But like his amendment to the reconciliation bill, Lees HOUSES Act lacked a definition of affordable housing, and critics suggested that it would lead to the building of mansions. In both 2022 and 2023, when Lee reintroduced the bill, it did not pass out of committee.But it caught the attention of Kevin Corinth, then the staff director on the Joint Economic Committee, which advises Congress on financial matters. After leaving the Capitol, Corinth joined the American Enterprise Institute, which began focusing on building housing on federal lands. This March, AEI held an event with powerful developers to discuss its ideas, which it called Homesteading 2.0. Edward Pinto, a former Fannie Mae executive who helps oversee AEIs housing research, said during the event that the proposal grew out of an effort that Sen. Lee undertook with the HOUSES Act.AEI advocates for dense development of single-family homes, but its ultimate vision remains opaque: The group has spoken of creating unregulated freedom cities far from existing infrastructure, and its proposals for 3 million houses seem ambitious. Headwaters Economics, a nonprofit group in Montana, published an analysis finding that existing public land could support less than 700,000 new homes; Nicholas Irwin, the research director for the University of Nevada, Las Vegas Lied Center for Real Estate, said he found Headwaters numbers more convincing.When I asked Pinto for a real-world example that illustrates his hopes for the West, he pointed to Summerlin, a planned community in Las Vegas, and Teravalis, a forthcoming development in Buckeye, Arizona, a rapidly expanding city at Phoenixs edge. Both are owned by Howard Hughes Holdings, a developer based in Texas.Housing in Summerlin is not easily attainable its median home price approaches $700,000. Teravalis, meanwhile, was first proposed more than 20 years ago and has been beset by delays, in part due to ongoing litigation with the state, which claims that the developer has not proven that it can obtain a sufficient water supply. A spokesperson for Howard Hughes Holdings, which bought the development in 2021, wrote that the company is working with local stakeholders around long-term water policy to support the full build out of Teravalis for more than 300,000 residents over several decades.Earlier this year, Pershing Square Holdings, which is controlled by the billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, purchased $900 million of stock in the company. (Ackman, a prominent supporter of Trumps 2024 campaign, is now the executive chairman of Hughes board of directors. Through a spokesperson, he declined to comment for this article.)Teravalis first lots sold for a steep $777,000 per acre without homes on them, and Hughes plans are for 2.8 dwellings per acre less than a quarter of the figure that Pinto cited as ideal for naturally affordable housing. Hughes is currently planning a grand opening for November. The company did not say how much homes would cost, but a spokesperson wrote in a statement, The need for new housing in the Phoenix West Valley is urgent, and Teravalis will help meet that demand. Edward Pinto of the American Enterprise Institute cited Teravalis, a planned community in Buckeye, Arizona, as the kind of development that could be built with sales of more public lands. (Adriana Zehbrauskas/The Washington Post/Getty Images) When given the option, developers often pursue the profit margins of high-end housing. In 1998, Congress passed a law, the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act, that allows any of the states municipalities to request the sale of federal lands for affordable housing. (SNPLMA relies on the Department of Housing and Urban Development to define affordable housing, which it says are units within reach of those making up to 80% of the areas median income.) Still, to date, only about 900 acres have been set aside for affordable housing projects under the law and only 30 of those acres have been developed into homes where low-income residents can actually live.Its unclear why so few affordable housing projects have been built at a time when they are so desperately needed. Clark County Commissioner Marilyn Kirkpatrick attributed it to bureaucratic delays: Its taken a long time to get through the process with the BLM. According to Maurice Page, executive director of the Nevada Housing Coalition, the average time the BLM takes to review projects has recently dropped from between three and five years to one. Only at that point can a developer close a deal. Tina Frias, CEO of the Southern Nevada Home Builders Association, said such delays can be crippling.In 2023, the BLM began selling Nevada land for affordable housing for $100 per acre. (Previous SNPLMA affordable housing sales had averaged nearly $35,000 per acre.) Still, local authorities have not requested the transfer of many parcels in recent years. According to the BLM, only three new affordable housing projects are moving toward approval.In a statement, a spokesperson for the agency wrote, BLM Nevada can only offer land after it has been nominated by an eligible entity and BLM has confirmed that there are no encumbrances or restrictions on the parcel. In many cases, the restrictions referenced by stakeholders originate with the nominating entities themselves.SNPLMAs affordable housing mechanism is also poorly understood. Alexis Hill, the chair of Washoe Countys board of commissioners, which includes Reno, told me she didnt know whether the affordable housing provision applied there. (It does.) When I asked Bidens former BLM director, Tracy Stone-Manning, who now leads The Wilderness Society, whether the $100-per-acre provision was applicable statewide, she said she did not know. Squillace, the Colorado law professor, also admitted he wasnt sure how widely the provision applied.Steve Aichroth, the administrator of the Nevada Housing Division, acknowledged a disconnect between agencies. His office is hiring an official to work with municipalities and the BLM. If you came back to us in about a year wed have better answers, he said.In the meantime, both of the states Democratic senators, Jacky Rosen and Catherine Cortez Masto, have proposed legislation that would open federal acreage for housing and transfer it to trust land for tribal nations while protecting other territory for conservation. The governor, Joe Lombardo, a Republican, recently signed a bill to invest $183 million of state money in developing housing for lower- and middle-class residents. Elsewhere in the West, New Mexico is leasing state lands to develop apartments. In Utah, the state housing office is encouraging cities to change zoning requirements to increase density; it is also using public funds to finance private developments and looking to build on state lands. Before Lee pulled his amendment, I spoke with Steve Waldrip, who directs housing strategy for Utah Gov. Spencer Cox. During our conversation, Waldrip expressed concern that the hyperpoliticized debate around a broad federal land sell-off was hampering focused efforts to alleviate the regions housing crisis. Theres no silver bullet thats going to solve the affordability crisis, he said.But some continue to believe a simple solution exists. After Lees amendment died, I spoke with Pinto, who directs AEIs efforts to push for housing on federal lands. He struck a conciliatory tone, given the political climate. (The sweeping GOP bill passed Thursday without Lees amendment.) At the moment, Pinto said, there doesnt appear to be an easy route to sell large swaths of public land for development. The path forward is to have a much more targeted approach.In Nevada, such a thing is already happening. Last year Clark County bought 20 acres from the BLM for $2,000, and the countys plan is to turn that land into single-family houses for first-time homebuyers. This spring, a new affordable housing development opened in Las Vegas an apartment complex for people 55 and older with rent starting at $573. The project was built by a developer called Ovation on former public land that was transferred through SNPLMA. It had taken a while the deal was first proposed in February 2020. But recently, the pace of transfers has picked up. Ovation says its also working on a similar project in the city of Henderson. It was nominated for BLM approval last February and, according to Jess Molasky, the companys chief operating officer, We hope to be in the ground in the first quarter of next year. Gabriel Sandoval contributed research.

0 Comments

0 Shares

119 Views

0 Reviews